Event Backbone

You are building applications that will follow an Event Driven Architecture. You have several disparate systems that all generate events and that need to respond to events.

Event driven systems have come in a number of different types and styles. From the very early days of the initial implementations of the Observer Pattern in Smalltalk through the various event systems in GUI frameworks like Microsoft Windows, Java’s AWT and Java Swing through the development of distributed event systems that operate over protocols like Apache Kafka, all event-driven systems have held some simple elements in common:

- The ability for some components to produce events of a certain type

- The ability of components to register to receive events of a particular type

- The ability of the event system itself to deliver events from 1. to 2.

The issue is that each of these elements has often “locked in” developers to particular solutions. For instance, in order to produce events in an implementation of the Observer Pattern the event provider (the Subject) would have to know about each of the event receivers (Observers) in order to deliver events to them. Likewise, many event systems require that when a receiver registers to receive events that the events that they receive be of the type (or structure) that is provided by the provider – regardless of whether or not that structure is meaningful to them. Finally, when we choose a particular event delivery system such as WS-Notification, we are often restricting ourselves to a particular mechanism of transport – usually HTTP in that case.

How do we develop systems so that the event producers and event consumers need not know about each other’s physical location, need not care about the details of the structure of the events produced or received, or be concerned about the event delivery mechanism?

We do not want to force users into a situation where a technology choice limits their possibilities for communicating events. For instance, if you choose to communicate all events exclusively through IBM MQ, then you limit yourself somewhat in communicating events to business partners on the global internet. Likewise, if you choose only an event notification approach such as WS-EventNotification, you may limit yourself to those applications that support SOAP Web Services.

Finally, you do not want to limit producers or consumers of events to one particular physical location from which to send or receive events. Encoding such location of event infrastructure into the consumer’s code limits its ability to scale and to deal with failure situations.

To address the problem, we must develop an Event Backbone that is responsible for the following things:

- It should support independence of physical location of event consumers and event providers. An Event consumer should not be aware of where the events are originally generated. An Event provider should not be aware of who receives its events, or how many receivers subscribe to its events. This can be achieved through the use of distributed messaging protocols.

- It should allow for multiple independent channels or topics that allow for the separation of different event types - receivers can choose to subscribe to those topics or channels that they choose and no more.

- It should allow receivers and providers to choose their own event structures. In order to support this it should allow for translation of event structures on the bus.

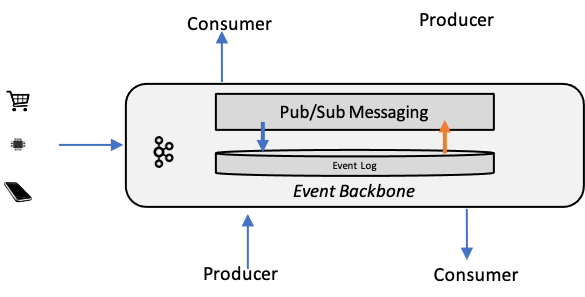

Many architectures use open source products such as Apache Kafka as some or all of the implementation of their Event Backbone. Kafka allows for location independence (it can even be run distributed across multiple sites) and allows for the specification of multiple event structures and topics. Likewise most major cloud providers support their own Event Backbones (see for example AWS EventBridge, IBM EventStreams, or Azure Event Hub). The basic structure of these systems is shown below.

Although not absolutely required to implement an Event Backbone, most of the above systems employ a combination of Publish-Subscribe Channels and a persistent Event Log to form the Event Backbone. The existence of a persistent Event Log makes Event Sourcing possible.

The implementation of an Event Backbone assumes the implementation of Event Consumers that are selective in the events they process. Putting in an Event Backbone will solve the immediate issues of location transparency but can then lead to further issues in overloading applications with a flood of events. The Event Aggregator pattern addresses this issue.